| claire barrow | victim of cosmetics

A few years ago, I asked my sister to buy me a ring light for my birthday. I’d been making

TikToks for months and had grown a following, but I was still chasing the sun and

crooking my arm until it was sore to get good lighting and a flattering angle. I became

conscious of how my pores appeared on camera and paths of tension around my mouth

when I talked, and I knew a ring light was supposed to make you look how people want

to look in videos — smooth skin, bright eyes, aging or acne blotted out, lit from within by

the glow of luminous plastic. After I received my ring light, I spent time flicking between

different levels of cool and warm and bright and dim, watching how they changed my

face in the view of my phone’s front-facing camera. I settled on a cool tone of medium

brightness, pleased with the way it smudged out all signs of life except the good ones

(pinched pink cheeks, a spot of light reflecting off the ball of my nose). As part of the

filming process, I’d sit cross-legged and do my makeup — usually a protective cat eye

with brown eyeshadow or drugstore black liquid liner that I could never quite get close

enough to the inside of my eyelashes. I sometimes used my phone’s front-facing camera

as a mirror, dipping into my makeup bag as I worked. Like all good makeup bags, mine

was a little dirty and pockmarked, a fine dust of mixed powder settled on matte-finish

palettes and tubes faintly tacky from unidentifiable leaks.

Last year, TikTok introduced the retouch feature, which made it possible to whiten your

teeth and smooth your skin on the app — the ring light’s ring light, Facetune for what

was previously the final frontier of face-editing. TikTok’s beauty filters also became more

beautiful. No more eyelashes that glitched away if you turned your head, or overripe

Bratz doll lips and cheeks that looked like a parody of plastic surgery. Now every week it

feels like there’s a new filter going viral for being too good at its job. A beautiful blonde

TikToker, recently photographed for Interview magazine, uses one such filter frequently

enough that there are hundreds of videos of girls trying it on to get her look (and almost

always making a comment about how the filter, in fact, did not make them look like her).

She got big on TikTok for her GRWMs, short for ‘get ready with me,’ in which she does a

full face of makeup while telling stories about last night, usually surrounded by the

discard of last night (and the night before, and the night before). Half-eaten Uber Eats,

shed hair extensions, skins of tried on or unwashed going-out clothes, makeup stand

barely visible beneath a landslide of cosmetics. Her room is like a beauty bog and she’s

the pearl in the slimy grey folds of an oyster.

She is 5.2-million-followers-beautiful but her room is frat-house-after-a-rager-gross. She

got a boob job before she graduated college, but she’s also on Accutane. She’s too hot

to be relatable, but she’s relatable enough to not know how to walk down a red carpet.

And like all women who are famous in any way these days, the way she looked before

and after she blew up is constantly examined for discrepancies (the difference is the

work done). “You’re not ugly, you’re just poor,” has become the rallying cry for not

comparing yourself to the rich and famous, but maybe that’s not the point anymore.

Maybe the point is, are you really that beautiful if there isn’t a before and after?

- GRWM, Biz Sherbert

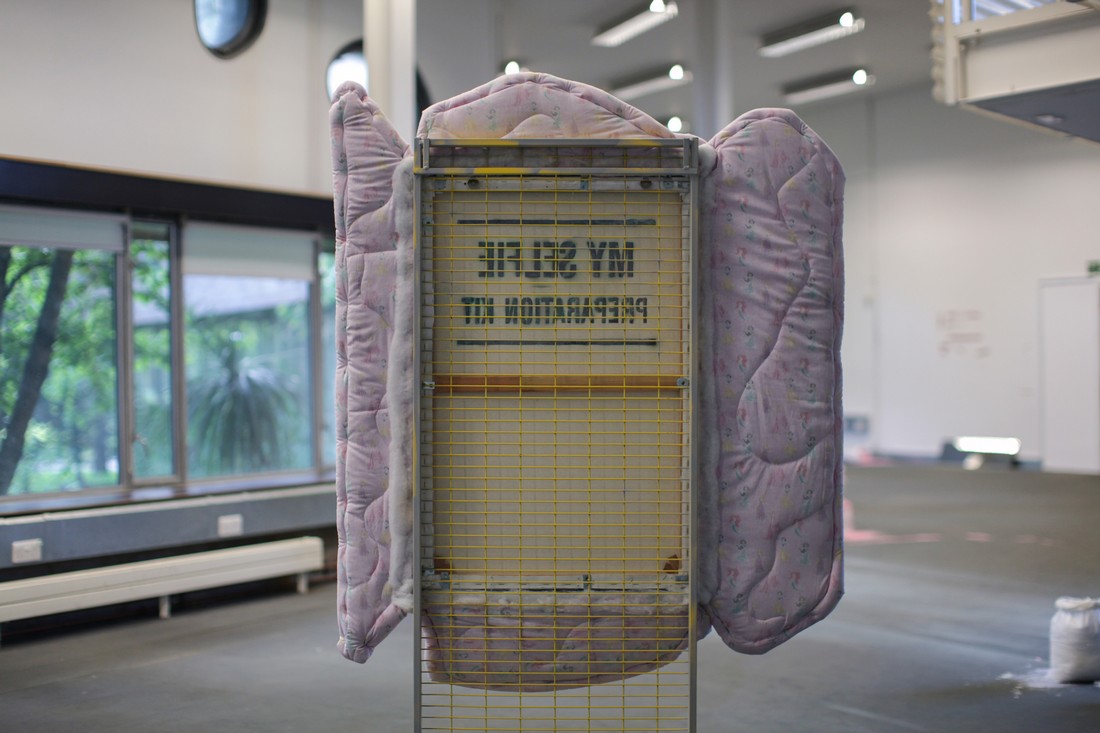

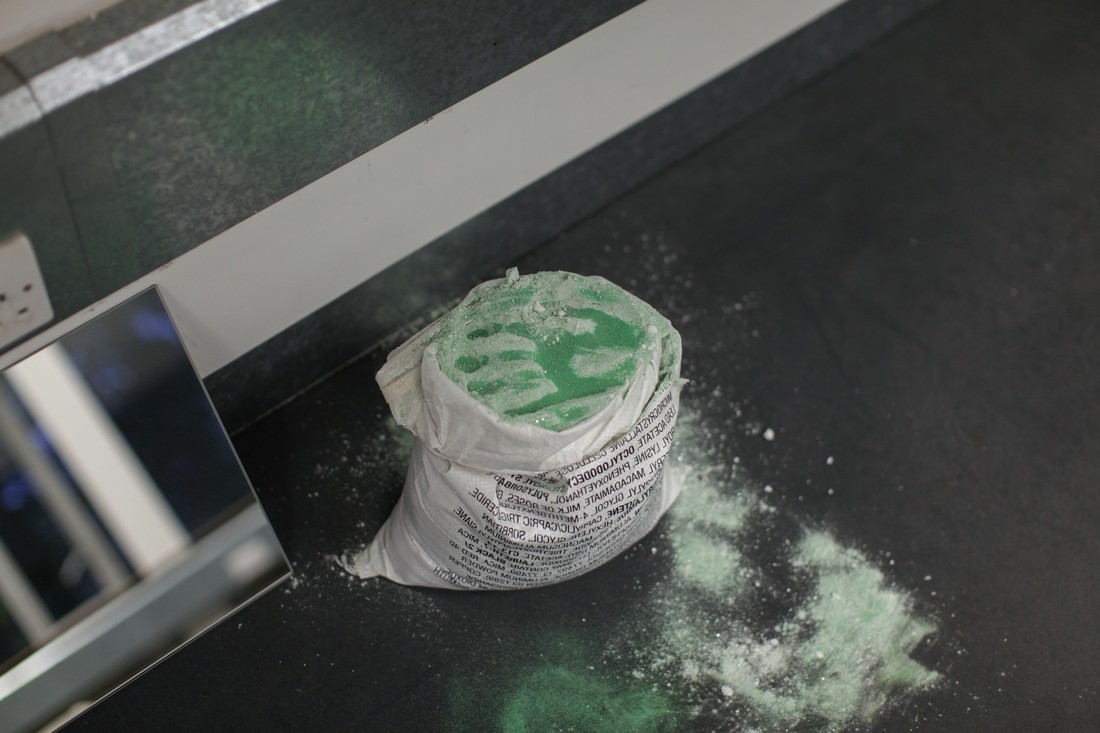

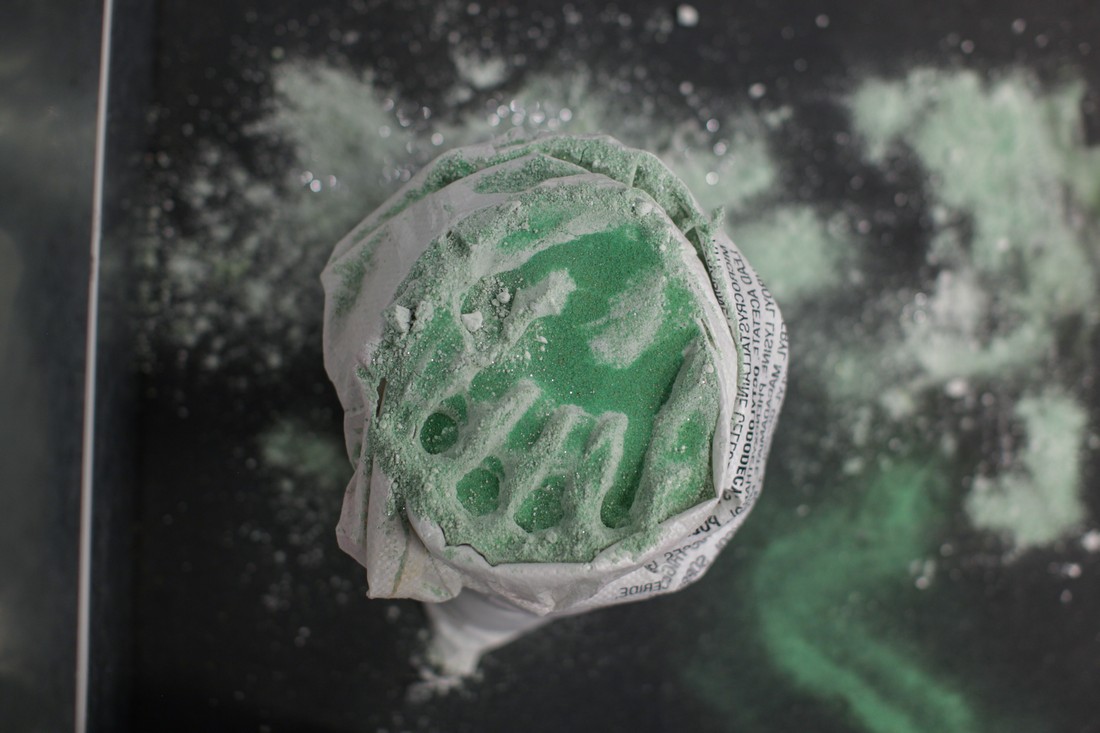

Claire Barrow is pleased to present Victim of Cosmetics, a solo exhibition showcasing

her new body of works presented in a repurposed office space in London Fields. Open

for two days only, the exhibition comprises a series of multi-media paintings and

sculptures which assemble into a zombie-commercial shop display of textiles, metal,

pigment and sand.

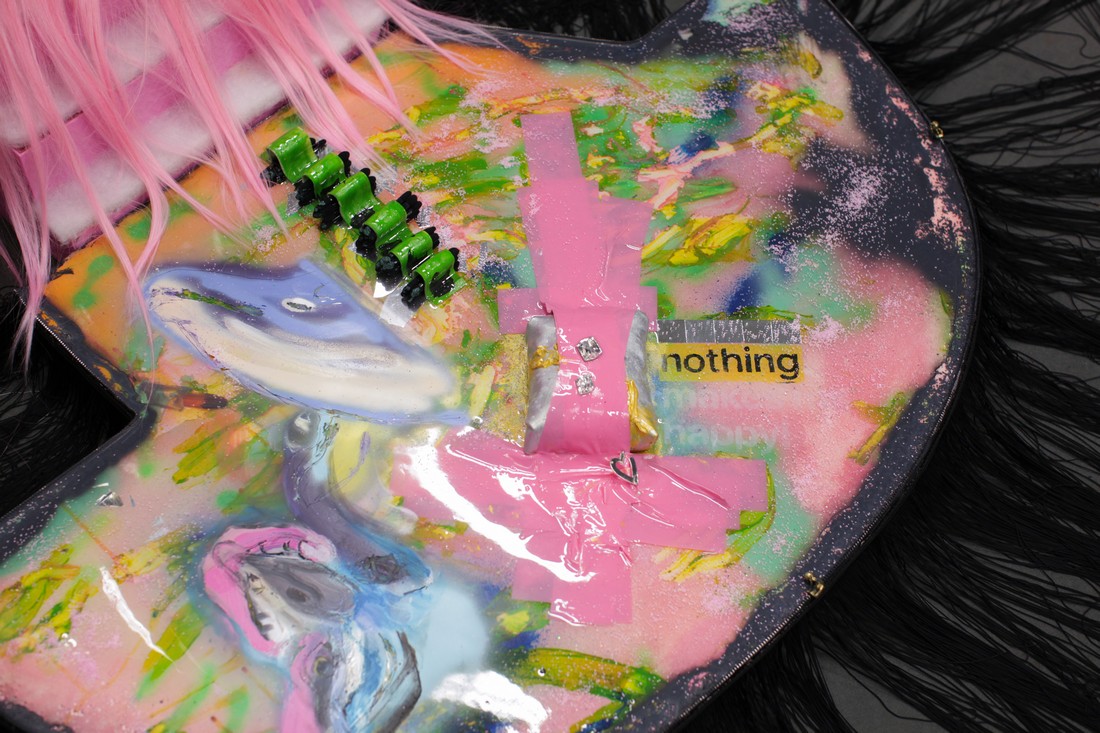

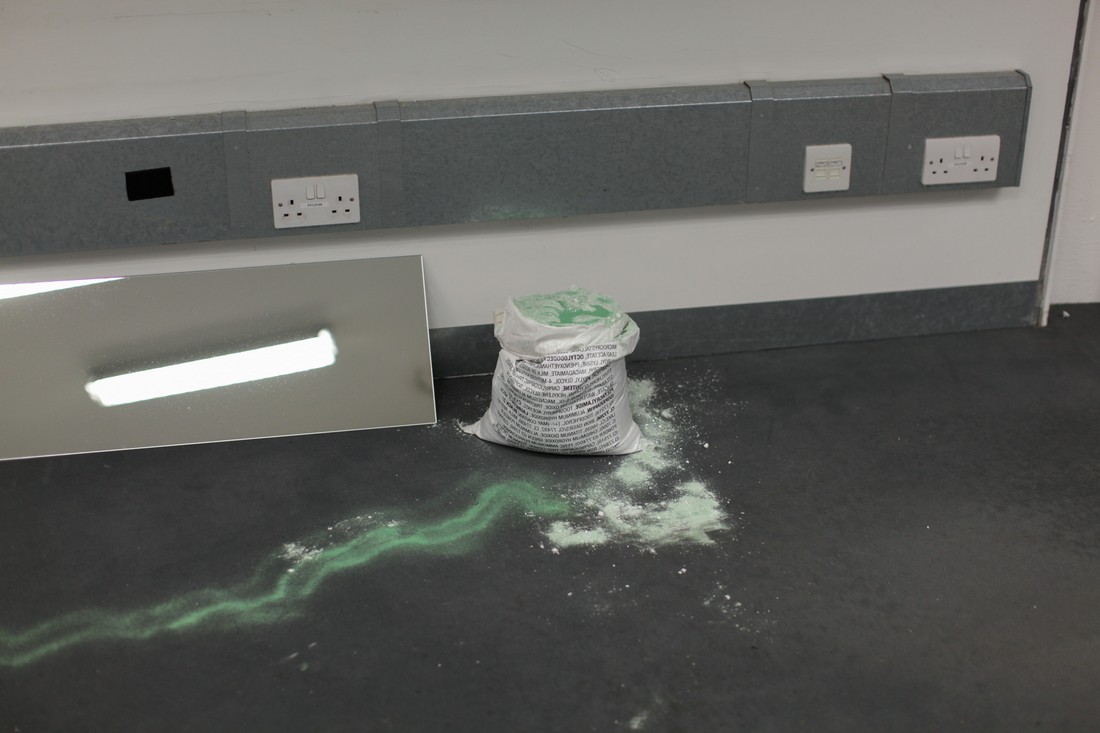

Concealing, blending and building up on her past in the fashion industry, Barrow guts the

materiality of commercial beauty to explore the patterns of its entrenchment in our needs

and identities. The pursuit of perfection, and, even moreso, augmentation, haunts the

mirroring halls with its many paranoid martyrs of self-actualisation.

Like a map of the world on the wall, the cosmetic bag folds out into an abstracted

blueprint of desire. Barrow stretched its skin – a cosmetic bag’s layout and the fabric of

its lining – into a type of shrine, the offering of a holy garment flipped inside out. Barrow’s

paintings are coated in resin, plastered with pigment and spray, framed with metal zips

and mounted on metal shop display units and ring lights like reflective obstructions. The

dirty tactile life of a bag’s innards – grease, pigment, residue – piles into the paintings

underpinned with the commercial innocence of princess-print cloth.

Mirrors reflect the sloganeering online language of self-realisation gleaned from the

Kardashians and Pinterest. In their mischief, one built of the same denial that allows

internet culture to turn anything into a joke, Barrow’s works are, as if, sad to mock the

power of sanctity.

Claire would like to thank; Dan Ross, Johanna Ruukholm, Lokikey, Sandra Dileep, Millie

Rose Dobree, Ewan Mennie, Liina Leo, Biz Sherbert, Tosia Leniarska & Daniel Swan

For enquiries, please contact studio@clairebarrow.co.uk

| claire barrow | victim of cosmetics

| claire barrow | victim of cosmetics  | claire barrow | victim of cosmetics

| claire barrow | victim of cosmetics