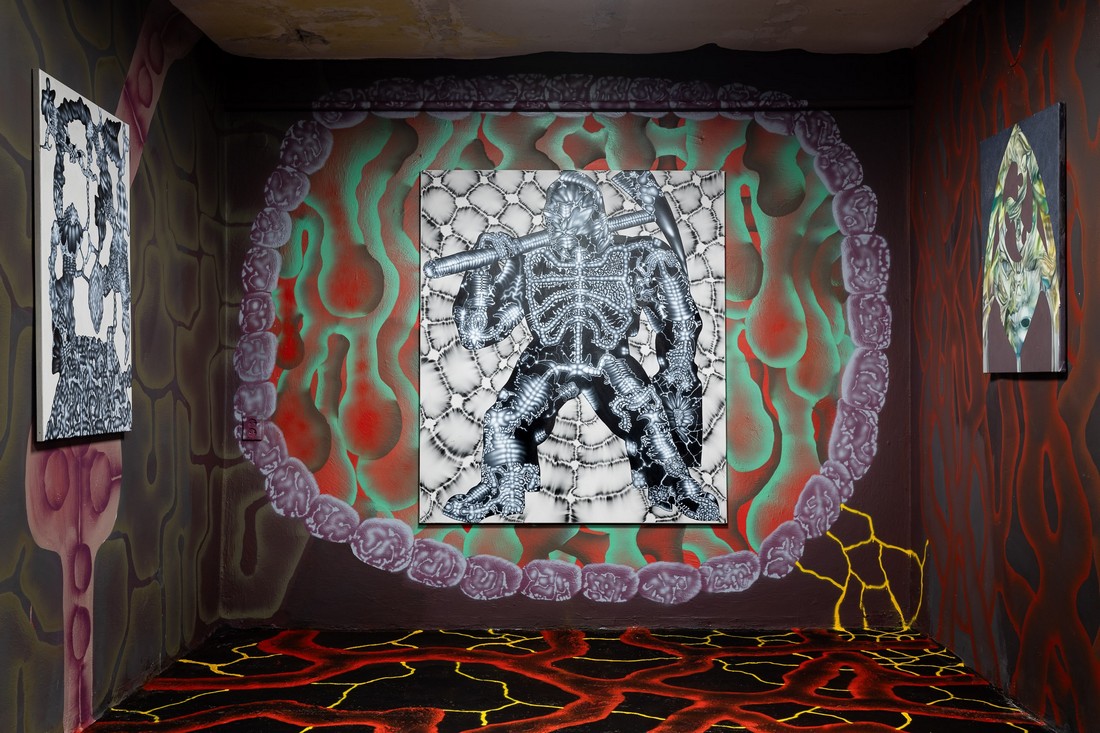

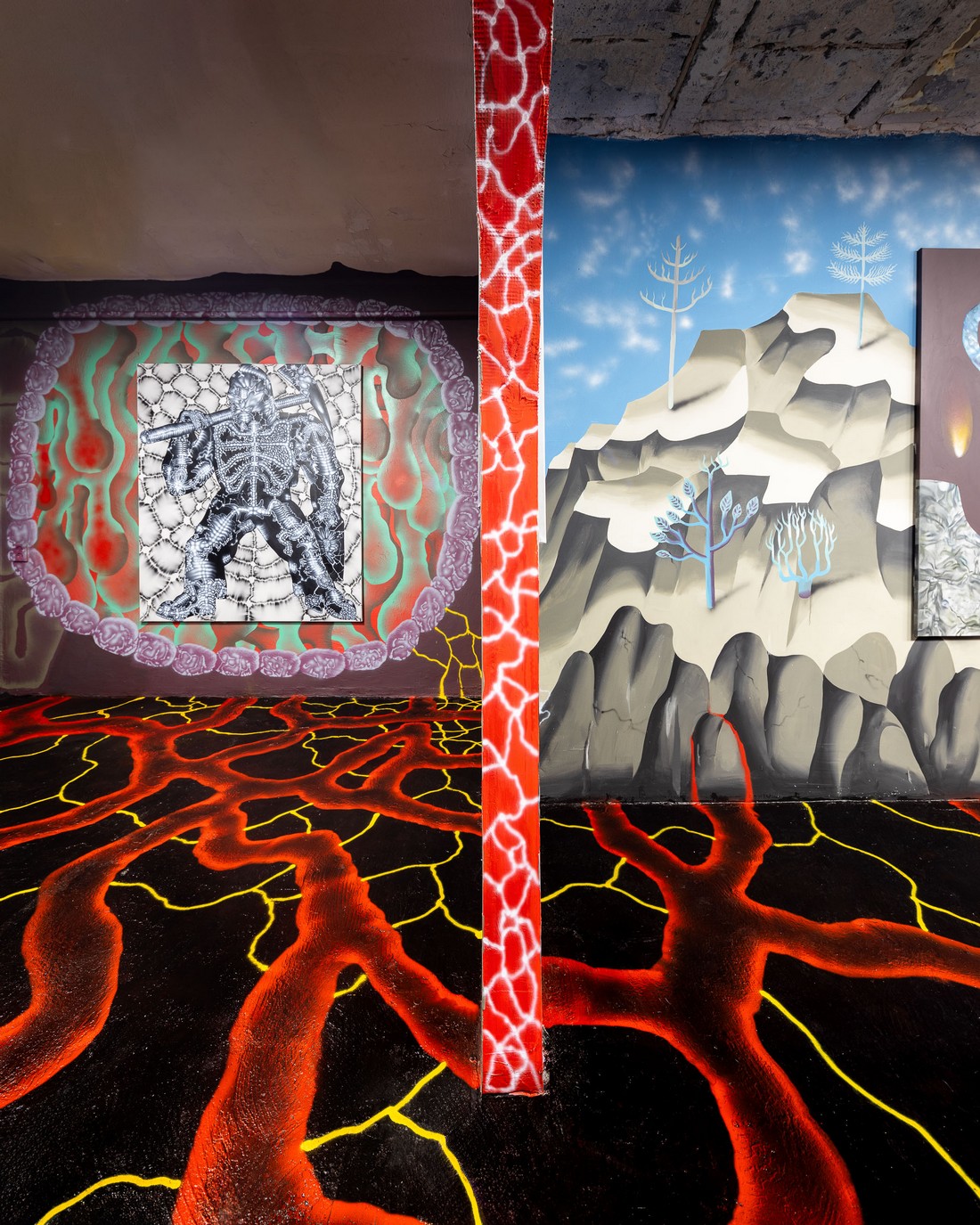

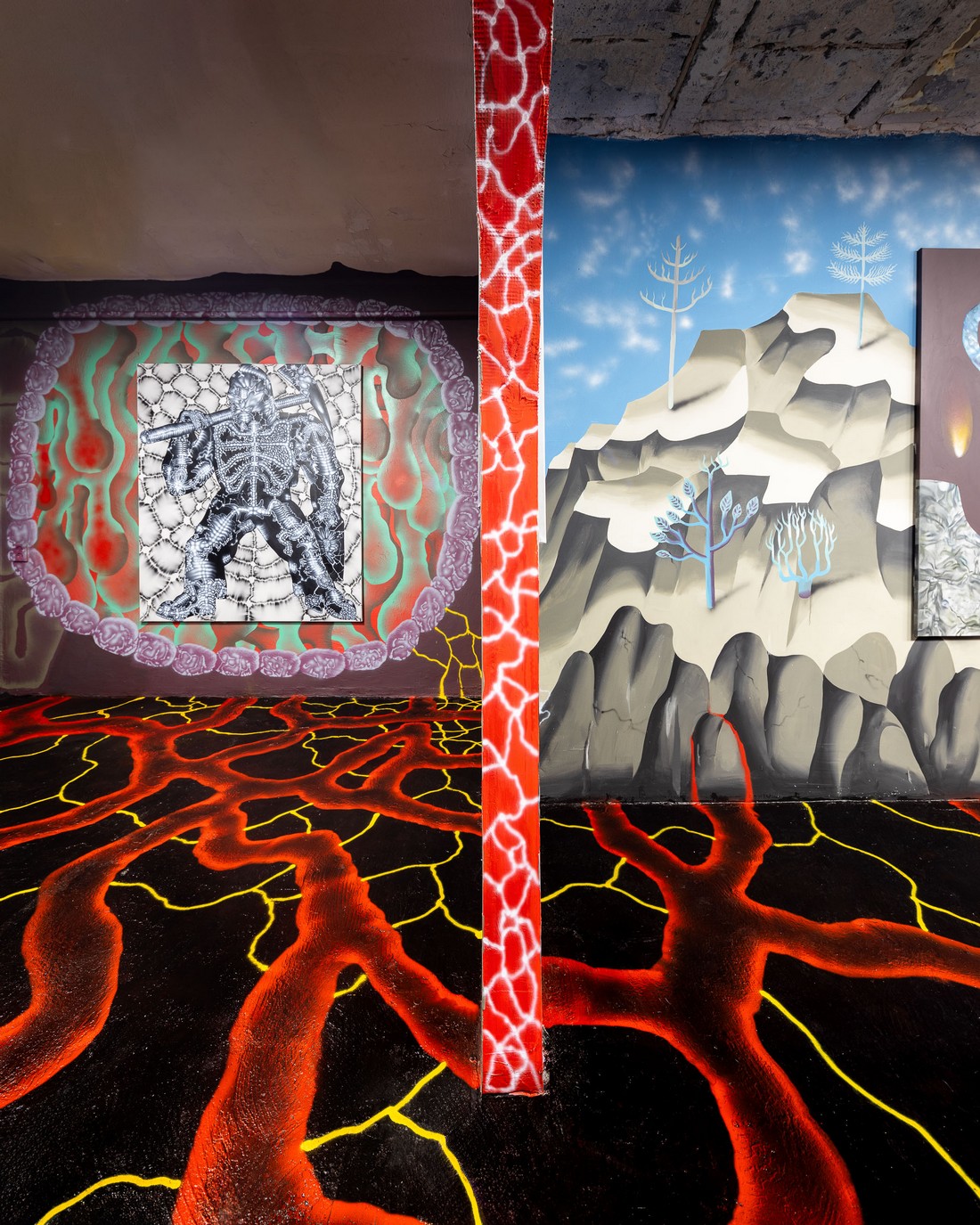

dungeon keepers | stach szumski + botond keresteszi| piana

This interview was conducted on the occasion of an exhibition at the Piana Gallery Foundation

titled Dungeon Keepers. The event marked the very first gallery-based collaboration between

Stach Szumski and Botond Keresteszi. Their inspiration stemmed from a common element in

their work - the undeniable urge to delve deeper into the layers of visual culture produced by

humankind. The exhibition takes the mesmerizing form of a mining map, skillfully guiding us

through a labyrinth of images entwined within a dense network of tunnels, each holding its own

unique association and profound meaning. In Stach's works, we find ourselves following the trail of natural textures and hypnotic organic shapes, suggestive of the exquisite decay that forms a natural stage of material transformation. Botond's work, on the other hand, resembles layers of anthropogenic sediments, allowing us to discern the historical strata of human activity. Each layer reveals an array of captivating images, sculptures, and objects hailing from diverse cultures and regions, weaving together a remarkable tapestry of human expression.

The conversation took place between Prague - Budapest and Michałowice on the 8th of June

2023

Piotr: I wanted to ask you about your collaboration since this is not the first project you have

worked on together. What is the nature of your cooperation and what were the occasions where

you have met before? Also, I’d like to ask about the moment when you saw each other's works

when the chemistry started to kick off.

Stachu: I had known Botond's work for a few years. Maybe I had seen your stuff around 2017 or

2018, I guess. I was kind of following it, more as a virtual kind of fandom and then we met

physically during the Graphic Biennale in Ljubljana in September 2021.

Botond: And then we hung out a lot there, and right after that, you came to Budapest for several

exhibition projects, including the one where we painted this wall together in November 2021 at

the AQB.

Stachu: Yes, Boti organized the wall at the Art Quarter Budapest space, where we had our initial

collaboration. It was a spontaneous improvised wall painting. Now, when I think about it, I

realize it was actually the only time we properly worked on one piece together.

Botond: That was when the idea of making an exhibition was brought up for the first time. From

my side, when I first saw your work, it was Mark Fridvalski who sent it to me and he said, "You

should check this guy. It's amazing. He's awesome using an airbrush." I checked your

Instagram account and realized that we were following the same graffiti accounts. All of a

sudden, I saw your likes everywhere. I call it a common taste. What left a big impression on me

back then were your gigantic murals in abandoned spaces, in rundown buildings - the Sudetten

Ziggurat. To me, it felt like some kind of post-Soviet shaman thing. I really loved that.

Piotr: Botond, do you also have some experience in graffiti?

Botond: I have been following this cultural phenomenon since the early 2000s. I was a teenager,

and I never went deep into this subculture, but I always knew what was going on, especially in

Hungary. During art studies, I made friends with graffiti writers, and we put together a crew and

bombed a small train or a wall. To this day, I have a special place in my heart for graffiti.

Stachu: In my case, it was the other way around - from graffiti to the art academy. Graffiti was

my entry-level activity. So, the first seven years of my artistic hustle were strictly outdoor-based.

I did a lot of small drawings, but spray paint remained my main tool. I was just exploring all the

abandoned factories in my region, as well as train lines, track sites, and all the railway-related

areas.

Piotr: Despite the differences in your backgrounds, you seem very enthusiastic about your

collaboration. Where does this enthusiasm come from?

Stachu: Yes, I believe that Botond and I have strong connections and a common approach

when it comes to the way we work with various forms and patterns. I think the key element is

this melting approach - the metamorphism of shapes and objects. In my case, this way of artistic

expression started around 2016 when I began painting with an airbrush. At that point, I was

experimenting with textures and patterns, distancing myself from a realistic basis and focusing

on endless variations. I believe we have this in common - this urge to melt, connect, and morph.

Botond: Yeah, I felt it when I returned to oil technique, which I had neglected for some years

after university. Once I came back to it, I consider it relevant also because it allows fluidity and

has a metamorphic structure encrypted within itself.

Piotr: When it comes to the process of morphing, it encompasses two distinct directions. On one

hand, there is the morphing that breathes new life into an entity, infusing it with fresh energy,

much like two trees intertwining and growing together. On the other hand, there exists a

morphing characterized by decomposition, akin to a parasitic mushroom leeching onto a host.

So, which aspect of morphing captivates you more?

Botond: Initially, my style leaned towards vibrant expressions. I employed fewer elements,

focusing on precision. Reflecting upon it now, I perceive my work as a digital photo collage

painted onto the canvas. As time progressed, I incorporated even more elements, widening my

range of inspiration. This newfound breadth allows for playful construction of meaning, which

gradually becomes more elusive and nebulous. Pinpointing a specific object within the painting

becomes arduous, giving rise to a sense of monstrous parasitic forms.

Stachu: I find myself in an intermediate realm. My artistic practice originates from the texture of

concrete, yet my approach is improvisational. I commence with predetermined patterns and

gradually add to them in a contingent manner. Naturally, they evolve into larger structures,

propelled by the principles of progress and development. Although abundant patterns of molds,

slimes, and fungus may be discerned, I believe my work retains an inherent life-oriented

essence.

Piotr: Perhaps the dichotomy of life and death is not entirely accurate, as nature, too, blends the

two seamlessly. Now, I'm curious about your fascination with caves, mines, and tunnels—the

connection you forge with the past embedded in the land.

Botond: In my case, it's really connected to my artistic statement, which is thinking about history

seen as layers in the cultural field. I'm really interested in different periods of art history and

visual culture history, from antiquity to modern design. It was fascinating for me to follow the

history of Heinrich Schliemann, who found Troy under twelve layers of cultural sedimentation.

My work is a melange of many sedimentation layers where you might find Bionicles and

children's toys, metal tools, and classical sculptures. You are welcome to dig in the fossils of

human culture.

Stachu: Plus, you are from a mining city, right? Tatabánya.

Botond: I wasn't born there; we just moved there when I was three years old. But mainly, my

whole childhood and teenage time I spent there. The mines were closed in 1993. My father

worked for a mine for a couple of years, but then the industry stopped, as in many regions of

Europe. On the hill next to the town, there is a massive limestone cliff where you can find a

huge cave with a giant hole in the ceiling through which you can see the sky. We used to hang

out there with friends after all the tourists were gone. It looks like a concert hall, and it could be

a perfect example of this Platonic cave. You can easily imagine the fire and the shadows there

with the moon shining from above.

Stachu: In my hometown in Karkonosze, there was an open-pit quarry of granite. So when I was

still a little kid, I could still feel the vibrations of detonations and the exploitative processes. It

was a day-to-day repetitive vibration caused by the explosions. They closed it when I was three,

yet I can still recall the sound and vibrations coming from the quarry.

Piotr: What about the infamous uranium mines in the region?

Stachu: There is one quite close to my hometown, just maybe ten kilometers away in a straight

line. It's the second-biggest uranium mine in the Eastern Block. They exploited the massive vein

of uranium, which is quite often present inside granite and appears inside the stone. The

exploitation lasted only for a decade. I remember only the atmosphere of the post-mining

environment.

Botond: I think it's very common with all of these post-Soviet countries that the mine is closed.

And during the 90s it's a new era came to stop coal mining.

Piotr: I think it was rather a matter of privatization and massive tunneling of state-owned

industries which for instance was very common in Czechoslovakia.

Stach: Do you think at any stage they cared for the environment?

Botond: Climate change wasn't a big topic back then but you remember for sure the phobia of

ozone holes. Have you seen the Highlander* movie, the second one when the sky was orange

because all of the ozone was gone? People lived under a huge coping - cupola-like. exposition.

Piotr: It looked like NYC now.

*Highlander II: The Quickening was a science fiction film released in 1991. The plot of the film takes place

in 2024 when air pollution caused the destruction of ozone in the atmosphere. Eventually, a crew of

scientists led by the main protagonist Connor MacLeod was able to create an electromagnetic shield to

protect the Earth. The protection saves the Earth but with the side-effects of condemning the planet to

constant darkness.

dungeon keepers

Stach Szumski and Botond Keresteszi

Piana Gallery (Kraków, Poland)

17.VI - 16.VIII.2023

{back}

dungeon keepers | stach szumski + botond keresteszi| piana

dungeon keepers | stach szumski + botond keresteszi| piana dungeon keepers | stach szumski + botond keresteszi| piana

dungeon keepers | stach szumski + botond keresteszi| piana